U.S.-Colombia Relations

Over the two centuries since Colombia’s independence, the relationship between Washington and Bogotá has evolved into a close economic and security partnership. But it has at times been strained by U.S. intervention, Cold War geopolitics, and the war on drugs.

U.S. Backs Panama’s Secession From Colombia

Residents of Panama, then a state of Colombia, launch a revolt against the central government after it refuses to grant the United States permission to build a canal over a six-mile-wide zone on the Panama Isthmus. The decision angers Panamanians, who would benefit from the revenue generated by a canal. U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt dispatches the gunboat USS Nashville to prevent Colombian troops from responding to the Panamanian rebellion. Washington soon recognizes Panama’s independence, and in 1904, the two countries ratify the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty, which gives the United States exclusive rights to the canal. In 1922, Colombia formally recognizes Panama after the U.S. government pays $25 million in compensation.

Hundreds Killed in Banana Massacre

Colombian employees of the United Fruit Company—a U.S. corporation with a local monopoly on tropical fruit—announce a strike to demand better working conditions on banana plantations. Fearing what it considers communist subversion, the U.S. government threatens to send in the Marine Corps should the Colombian government fail to protect United Fruit. The Colombian army opens fire on a crowd of workers, killing up to two thousand people. (The final death toll remains unknown.) The incident damages the reputation of Colombia’s ruling Conservative Party and sparks renewed outrage from the opposition Liberal Party over the role of the United States in Latin America, where commercial and military interests have been driving U.S. intervention, predominantly in Central America, during the Banana Wars period.

World War II Deepens Security Cooperation

Colombia, which was already permitting U.S. air and naval bases on its territory, declares war on the Axis powers, laying the foundation for decades of security cooperation with Washington. Bogotá later sends troops to fight in the Korean War, and Colombia is one of the first countries to send officers to the U.S. Army’s School of the Americas (SOA) in the Panama Canal Zone, where Latin American soldiers and police receive U.S. military training. The school later faces criticism over a pattern of human rights abuses [PDF] and the involvement of many of its students in coups, death squads, and drug trafficking, including in Colombia. Public pressure to close the school mounts after the Pentagon releases several SOA training manuals featuring descriptions of methods of torture, blackmail, and extortion. In 2000, it is rebranded as the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC).

La Violencia Sows the Seeds of Insurgency

The assassination of Liberal Party presidential candidate Jorge Eliecer Gaitan in 1948 spawns an outbreak of urban riots known as El Bogotazo and ignites La Violencia, a decade-long civil war between the country’s Conservatives, who are backed by the military and large landowners, and Liberals, who are allied with a constellation of socialist reformers, peasant rebels, and communist insurgents. Over the next ten years, the conflict kills an estimated two hundred thousand Colombians and displaces nearly one million. Washington seeks to maintain its neutrality while continuing to provide military and economic support. A power-sharing agreement ends the war, but the exclusion of communist groups and a power vacuum in much of the countryside soon gives rise to the formation of Marxist guerrilla groups.

‘Alliance for Progress’ Seeks a New Era

In the wake of Fidel Castro’s 1959 Cuban revolution, the U.S. government aims to curb the spread of communism in Latin America by bolstering economic and political development, including through programs such as President John F. Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress. Colombia becomes a major recipient of aid under the program, receiving millions of dollars worth of loans to finance projects promoting peaceful social change in areas such as infrastructure development and land and tax reforms. However, some critics of the initiative [PDF] argue that the aid prioritizes short-term financial goals over long-term reform, and the program ends in 1973.

Plan Lazo Creates Counterinsurgency Blueprint

In response to the persistence of armed guerrilla groups in the countryside, U.S. military advisors, led by General William P. Yarborough, work with the Colombian army to develop a comprehensive counterinsurgency strategy known as Plan Lazo (the Snare Plan). The plan centers on public works projects, civilian defense networks, and an aggressive military assault on “independent republics” formed by communist insurgents during La Violencia. Plan Lazo becomes the template for decades of counterinsurgency and civic action programs in Colombia.

The FARC and ELN Form

The push to stamp out the remaining pockets of insurgency spurs guerrilla leaders to formalize their operations, creating Colombia’s most consequential rebel groups, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army (ELN). Both groups, inspired by Castro’s success in Cuba, seek to overthrow the Colombian government, though the FARC is a mostly peasant movement and the smaller ELN draws its support largely from urban student and intellectual circles. The groups’ influence and territory grow through involvement in the drug trade, and by the 1990s, the FARC’s nearly twenty thousand members control around 40 percent of Colombia. The groups’ escalating acts of violence, kidnapping, and extortion eventually lead Washington to label them foreign terrorist organizations (FTOs) and prompt a decades-long U.S.-Colombia military and diplomatic partnership to combat them.

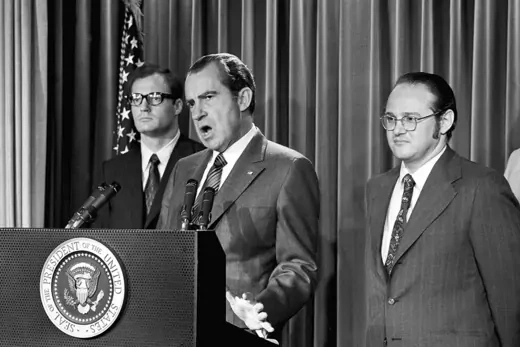

War on Drugs Comes to Colombia

By the 1970s, Colombian drug producers, who began by growing marijuana, expand into the production of cocaine, made from the native coca plant. Profits are immense, with Colombian cocaine selling for as much as $50,000 per kilogram in the United States. In 1971, U.S. President Richard Nixon requests $84 million from Congress to fund a global war on drugs, an effort that will eventually cost the United States more than $1 trillion. Colombia is the first target of this U.S. policy shift away from counterinsurgency in Latin America and toward counternarcotics, and Washington coordinates closely with the Colombian National Police to reduce illegal drug production and trafficking, including by eradicating coca fields and interdicting smugglers.

Cartel and Paramilitary Violence Escalates

The United States increases military assistance to the Colombian government, which is grappling with a growing conflict with rival drug cartels, as well as guerrilla groups and paramilitaries profiting from the drug trade. Bogotá blames the Medellin Cartel for the December 1989 bombing of the headquarters of the nation’s top security agency, which kills more than fifty people, as well as for the downing of a Colombian jetliner a month earlier. The rise in violence continues to spur the growth of right-wing paramilitary groups, such as the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) [PDF].

Leaders Hold Andean Drug Summit

In the wake of the bombing in Bogotá, the presidents of the United States, Bolivia, Colombia, and Peru meet in Cartagena, Colombia, to discuss counternarcotics cooperation. By this point, the cocaine trade is valued at nearly $10 billion per year, with Colombia responsible for around 43 percent of global production. As part of the summit’s final declaration, the four countries pledge to adopt [PDF] an anti-narcotics program focused on “demand reduction, consumption, and supply.” The U.S. Defense Department’s role grows, providing intelligence and military training and equipment to Colombian security forces and overtaking leadership in this area from the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). Between 1990 and 2000, the United States provides $1.6 billion in security assistance to Colombia.

U.S. Singles Out Colombia

Citing a lack of cooperation and endemic government corruption, U.S. President Bill Clinton decertifies Colombia as a partner in the drug war, a step that renders Bogotá ineligible for much U.S. economic aid, though counternarcotics assistance continues. Washington also revokes President Ernesto Samper’s visa, pointing to his alleged acceptance of campaign financing from the Cali Cartel. Samper’s administration criticizes what it sees as U.S. hypocrisy in singling out Colombia—and not Mexico, whose efforts are also considered inadequate by some U.S. officials—given the United States’ status as the largest consumer of Colombian cocaine. Meanwhile, as Colombia’s criminal underworld fragments following the 1993 death of drug lord Pablo Escobar and the subsequent dismantling of the Cali Cartel, the drug trade becomes increasingly decentralized.

Plan Colombia Seeks to Restore Order

As violence, kidnappings, and drug trafficking escalate, and as the FARC’s influence grows, President Clinton signs into law Plan Colombia [PDF], a new bilateral strategy aimed at helping Colombian forces in restoring order. Amounting to $10 billion in assistance over sixteen years, the plan has three major prongs: ending illegal drug production and trafficking, promoting economic and social development, and funding and training the Colombian military. The plan’s militarized approach earns bipartisan support in the U.S. Congress, but critics later argue that the dependence on Colombian security forces undermines its development goals, exacerbates environmental damage, and leads to human rights abuses.

Bush Launches Andean Regional Initiative

In the wake of U.S. President George W. Bush’s declaration of a global war on terrorism, Washington begins to reset its efforts in Colombia under the banner of counterterrorism. President Bush’s Andean Regional Initiative, which consists of an additional $882 million in military and economic aid to seven South American countries, further bolsters U.S. military support under Plan Colombia. With the FARC, ELN, and other guerrilla groups already on the State Department’s FTOs list, Washington and Bogotá seek to regain the offensive against such “narcoterrorist” groups, an effort that is championed by President Alvaro Uribe, who takes office in 2002.

Trade Talks Highlight Labor Issues

The Bush administration starts negotiations on a trade agreement with Colombia, called the U.S.-Colombia Trade Promotion Agreement (CTPA). The deal seeks to eliminate tariffs and other barriers to trade in goods and services between the two countries, including on agricultural and industrial products, financial services, and telecommunications. They sign a deal in 2006, but the U.S. Congress holds up ratification over concerns about weak labor and environmental provisions amid ongoing violence, especially against trade unionists. Congress approves a renegotiated deal in 2011 after President Barack Obama presses Bogotá for stronger labor protection measures.

Uribe Implicated in ‘Parapolitics’ Scandal

The revelation of connections between right-wing paramilitary groups and Colombian politicians, including President Uribe, Uribe’s brother, and members of Congress, shakes the country’s political class. The scandal underscores the degree to which paramilitaries, which, along with the Colombian army, are implicated in thousands of extrajudicial murders, are able to wield influence through bribes and intimidation. The revelations stir concern in the U.S. Congress, where the U.S.-Colombia trade deal is still pending ratification. To salvage the deal and demonstrate Colombia’s commitment to anti-narcotics efforts, the Uribe administration extradites fourteen former paramilitary leaders to the United States to face drug charges.

Colombia Hosts Regional Summit

The sixth Summit of the Americas, a gathering of the members of the Organization of American States, is held in Cartagena, the first time Colombia plays host to the summit. Several bombings in Bogotá and Cartagena in the days before the meeting spark fears about renewed violence, though no one is injured. Discussion at the summit centers on trade, Cuba, and the global war on drugs, with Santos and several other leaders criticizing the costly and ineffective militarization of the drug fight. Among the alternatives endorsed by leaders is drug legalization, though it is opposed by President Obama, who is in attendance. The summit ends with the heads of state pledging to focus [PDF] on mitigating the effects of natural disasters, promoting infrastructure investment, and eradicating regional poverty, among other efforts.

Colombia Marks Historic Move Toward Peace

The FARC and the Colombian government conclude four years of negotiations, hosted by Cuba, with the signing of a peace deal in August 2016 that aims to end fifty-two years of conflict that killed more than 260,000 people. After voters reject the initial deal in a national referendum, the two sides agree to revised terms that include an immediate cease-fire, disarmament, and the creation of a transitional justice system. In exchange, the FARC are recognized as a legitimate political party with ten guaranteed seats in Congress until 2026. Despite not having a formal role in the peace process, the United States supports it through the work of a special envoy, and President Obama proposes a $450 million aid package as part of his new Peace Colombia initiative.

Duque Shifts Policy Priorities

Ivan Duque, who ran on a platform critical of the peace accords, takes office as Colombia’s president and suspends existing talks with the ELN, citing the group’s continued violence and failure to comply with agreements made during the Santos administration. Duque finds an ally in U.S. President Donald Trump, who criticizes Santos for “surrendering to the narcoterrorists” by signing the 2016 peace deal. With Trump’s backing, Duque returns Bogotá’s policy focus to counternarcotics, as Colombia’s cocaine production is valued at around $2.7 billion and the United Nations estimates coca cultivation is at an “all-time high.” The two countries later reaffirm their commitment to cutting coca cultivation and cocaine production by half over the next five years.

Trump Pressures Duque at White House

In their first meeting, President Trump pressures Duque to step up counternarcotics efforts and resume the aerial fumigation of coca crops, a practice suspended in 2015 over health concerns. The two also discuss efforts to support Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guaido and respond to the ongoing Venezuelan refugee crisis. Meanwhile, at home, Duque faces growing public discontent over government corruption, his proposed tax reforms, and his lack of support for the 2016 peace deal. Sporadic protests erupt across the country as Duque’s approval rating plummets. Colombia also experiences a renewal of political violence from ELN and FARC dissident groups that reject the negotiated settlements with the government.

Crackdown on Protesters Sparks Criticism

Tens of thousands of Colombians take to the streets in late April to protest a revised set of tax proposals after earlier legislation failed in 2019. The bill, which would subject more households to higher taxes, is withdrawn within days, but the protests escalate. In response to reports of police brutality during the demonstrations—in which dozens of people are killed—a group of fifty-five Democratic members of the U.S. Congress condemn the government crackdown, with some calling for stronger conditions to be placed on U.S. security aid to Colombia. The State Department exhorts Colombian security forces to exercise the “utmost restraint.” Though President Joe Biden issues no direct statement, he later raises the issue with Duque in a call that focuses on the resurgence of violence in the country.

U.S. Removes the FARC From Foreign Terrorists List

Five years after the peace deal with the FARC was signed, Biden removes the rebel group from the State Department’s list of FTOs, which they have been on since 1997. Secretary of State Antony Blinken says the move will make it easier for the United States to support the full implementation of the peace accord, which continues to languish as the year is on track to be Colombia’s worst for homicides since 2013. The Biden administration also designates two breakaway groups created by former FARC rebels as FTOs: Segunda Marquetalia and the FARC-EP.

Biden and Duque Celebrate Bicentennial

During a meeting with Duque at the White House, Biden announces that the United States is designating Colombia a major non–North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) ally in recognition of two hundred years of diplomatic ties. The designation grants Colombia access to certain economic and security programs but does not automatically create a mutual defense pact with the United States. The two leaders also discuss the status of bilateral counternarcotics efforts and a potential new framework for managing regional migration, which is later launched in June at the ninth Summit of the Americas in Los Angeles. Biden also announces that the United States is donating an additional two million COVID-19 vaccines to Colombia.

Trump Steps up Trade Threats Over Deportation Flights

In response to Colombia’s decision to turn away U.S. planes carrying Colombian deportees, President Donald Trump threatens escalating tariffs on Colombian goods, starting at 25 percent, as well as travel and visa bans. Colombian President Gustavo Petro responds with retaliatory tariffs and says Bogotá will not accept any deportation flights until the Trump administration treats migrants with “dignity and respect.” After several tense hours, Colombia’s foreign ministry announces it would accept all deportation flights and use the presidential plane to help transport returning migrants.

Online Store

Online Store