Eastern Congo: A Legacy of Intervention

The Democratic Republic of Congo has been subjected to centuries of international intervention by European powers, as well as its African neighbors. This timeline traces the role of the outside forces that have beleaguered eastern Congo since the end of the colonial era.

Congo Achieves Independence

A newly independent Congo is created after nearly eighty years of Belgian control, and independence leader Patrice Lumumba becomes the country’s first democratically elected prime minister. Belgian colonial rule leaves the young country particularly unequipped to stand on its own: upon independence, Congo counts sixteen university graduates and a dysfunctional army with an untrained officer corps. Belgian colonizers had ruled the vast country through the feared Force Publique, which enforced rubber quotas and other economic production targets through torture, murder, and rape, leading to the deaths of some ten million people.

The First Congo Republic and Civil War

Lumumba immediately faces multiple crises. Days after independence, in July 1960, an army mutiny sparks a series of events that pushes the country into civil war. When the wealthy southern state of Katanga secedes on July 11, Belgian troops intervene to protect Belgian colonists and support the Katangan rebellion. A UN peacekeeping mission, ONUC, fails to restore order, leading Lumumba to appeal to the Soviet Union for military assistance. Lumumba is deposed in September 1960 and arrested by the Congolese military. He is later killed by secessionist forces with the alleged complicity of the U.S., Belgian, and British governments. UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold dies in an airplane crash while en route to mediate the crisis, leading to suspicions that he was assassinated. The subsequent power struggle between the Belgium-supported central government and pro-Lumumba insurgents in eastern Congo persists until the rebellion is defeated with the help of Belgian and U.S. forces in 1964.

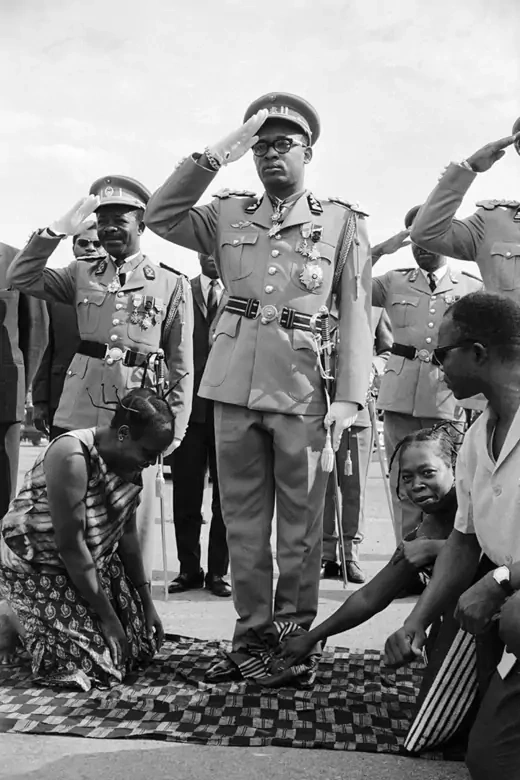

Mobutu Takes Power in Coup d’État

General Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, the young officer responsible for the 1960 coup against Lumumba, seizes power in 1965. President Joseph Kasa-Vubu and Prime Minister Moïse Tshombe flee the capital, Leopoldville (now Kinshasa), as Mobutu orders the public execution of several high-profile opponents and abolishes political parties. Despite promising a return to democracy within five years, Mobutu, now using the name Mobutu Sese Seko, rules with an iron fist for the next three decades. He seeks to expunge any foreign influence on the country through what comes to be known as “Zairianization”: changing the name of the country to Zaire (in reference to a native word for the Congo River), renaming and reorganizing cities and provinces, nationalizing farms and mines owned by foreigners, discouraging Western-style dress, and fostering a cult of personality around himself.

Mobutu Puts Down Rebellions With Outside Support

Beginning in March 1977, Congolese rebels based in neighboring Angola cross the border into southern Katanga (renamed Shaba) Province to foment an anti-Mobutu uprising. Outnumbered, the rebels succeed in taking the major southern mining town of Kolwezi from the poorly equipped Zairian Armed Forces (FAZ). Mobutu is able to defeat the uprisings only thanks to funding from the United States and the direct intervention of Belgian, French, and Moroccan forces. Western powers see defeating the communist-allied rebels and bolstering Mobutu’s rule as an important Cold War objective given Soviet and Cuban support to neighboring Angola’s socialist government, which the United States opposes.

Rwandan Genocide Pushes Millions Into Eastern Zaire

The four-year Rwandan civil war between the Hutu-led government and Tutsi insurgents comes to a head when as many as one million people, mostly Tutsi, are slaughtered over a period of one hundred days. The genocide ends with the July 1994 military victory of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), the Tutsi rebellion led by future President Paul Kagame, over the Hutu Rwandan Armed Forces (FAR). The RPF victory sends as many as two million Hutu—including more than thirty thousand Hutu ex-FAR soldiers—fleeing across the border to eastern Zaire. The Hutu refugees are packed into camps outside the major cities of Bukavu, Goma, and Uvira. In the camps, disease, malnourishment, and violence kill at least fifty thousand Hutu in the first few weeks, leading to a major UN humanitarian mobilization.

Rwanda-Led Forces Invade Zaire

Rwandan Hutu ex-FAR fighters in Zaire, seeking to return to power in Rwanda, use the refugee camps as bases from which to step up incursions [PDF] into Rwanda throughout 1995 and 1996. In response, the Rwandan government organizes a rebellion to attack the Hutu militias in Zaire and overthrow the Mobutu regime that is sheltering them, placing the Congolese rebel leader Laurent-Désiré Kabila at its head. The rebellion, known as the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire, or AFDL, allies with a regional anti-Mobutu coalition that includes Angola, Uganda, and Zimbabwe in what becomes known as the First Congo War. It is also referred to as the African World War, due to the many countries involved. AFDL forces capture eastern Zaire’s largest city, Goma, on November 1, breaking up refugee camps and killing tens of thousands of refugees and other civilians. The fighting causes hundreds of thousands of Hutus to flee deeper into the Zairian jungle and sends more than a million refugees back into Rwanda.

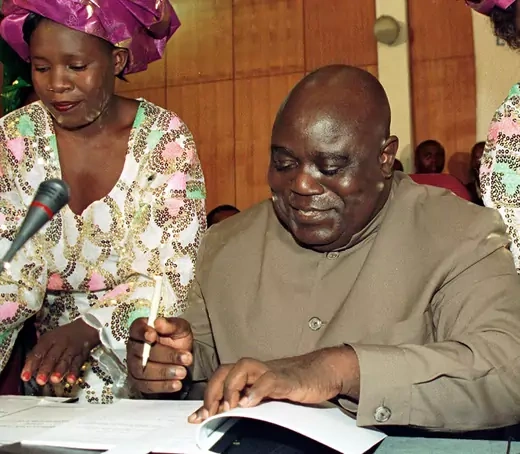

Mobutu Flees, Kabila Takes Kinshasa

Rebel AFDL forces sweep across the country as Mobutu’s national army crumbles. Six months after the uprising begins, Mobutu flees the country for exile in Morocco, and Kabila enters the capital, Kinshasa, on May 20. Sworn in as the new president on May 29, Kabila faces the task of governing a country reeling from decades of mismanagement with an economy shrunk to a third of its 1960 size, inflation at 750 percent, plummeting mining and agricultural production, and a depleted treasury. Kabila renames the country the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), suspends all political parties, and begins ruling by decree. He promises elections within two years.

Second Congo War Breaks Out

In July 1998, Kabila expels all foreign soldiers, most of whom are his former Rwandan allies, marking the end of the AFDL alliance. In response to their expulsion and continued Hutu rebel attacks from eastern Congo into Rwanda, Rwandan forces once again invade eastern Congo on August 2, 1998, with the support of Congolese Tutsis and others in the DRC army who also oppose Kabila. The Second Congo War pits Burundian, Ugandan, and Rwandan forces (which together with eastern Congolese rebels form the Congolese Rally for Democracy, or RCD) against Kabila and his backers. Kabila’s supporters include the governments of Angola, Namibia, and Zimbabwe, as well as local self-defense forces and the remaining Hutu ex-FAR soldiers.

Regional Powers Agree to Lusaka Cease-Fire

With the help of his foreign allies, Kabila contains the Rwanda- and Uganda-backed RCD rebellion to the eastern half of the country, but the government controls only the western provinces. As a result of the stalemate, the six main countries involved in the war—the DRC, Rwanda, Uganda, Zimbabwe, Angola, and Namibia—agree to a cease-fire on July 10, 1999. The Lusaka Accord calls for an immediate cessation of hostilities, the withdrawal of foreign troops from the DRC, the disarmament of militias, and the deployment of a UN monitoring and peacekeeping force. However, the domestic anti-Kabila rebel groups ignore the agreement and the Rwandan and Ugandan branches of the RCD splinter and begin fighting one another for territory and resources in eastern Congo.

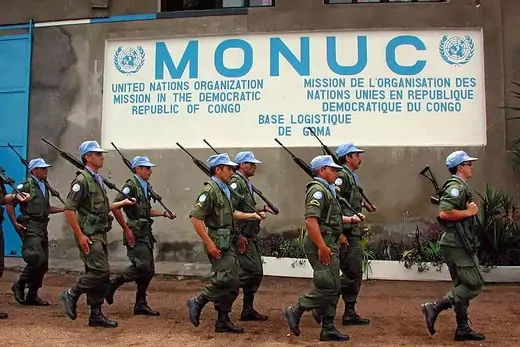

UN Launches Monitoring Mission

The UN Security Council establishes the UN Organization Mission in the Congo (MONUC) to monitor the cease-fire. Through Resolution 1291, MONUC’s initial authorization provides for 5,537 troops and 500 additional military advisors; it will later grow to more than 22,000 uniformed personnel. The UN mission is limited to a primarily observational mandate: liaising with the various military factions in eastern Congo and throughout the country, verifying the demobilization of forces, and facilitating humanitarian assistance. MONUC is also tasked with protecting civilians “under imminent threat of physical violence.”

President Kabila Is Assassinated

Kabila is assassinated by his bodyguard, twenty-year-old Rashidi Kasereka. Ultimate responsibility for the killing remains unclear, with conflicting evidence pointing to the involvement of Rwanda, Angola, and Kabila’s disgruntled former child soldiers. On January 26, the cabinet appoints Kabila’s twenty-nine-year-old son, Joseph Kabila Kabange, to the presidency. Joseph Kabila immediately moves to restart the Inter-Congolese Dialogue peace process, meeting with Rwandan President Kagame in February 2001, supporting the cease-fire, and welcoming an expanded UN presence in the DRC.

DRC and Rwanda Sign Peace Deal

Joseph Kabila and Rwanda’s Kagame sign a peace agreement in Pretoria, South Africa. Mediated by South African President Thabo Mbeki and UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, the Pretoria deal gives Rwanda three months to withdraw tens of thousands of its troops from eastern Congo. In return, Kabila agrees to disarm the nearly ten thousand Rwandan Hutu fighters still in the region and repatriate their leaders to Rwanda to stand trial. MONUC will also expand its presence in the east and assist with the demobilization of militias.

Warring Parties Sign Power-Sharing Agreement

After months of talks, all of the major domestic rebel groups—the RCD in the east, the Mobutist Movement for the Liberation of the Congo (MLC) in the north, and the local self-defense forces known as the Mai Mai—come to a power-sharing agreement with the DRC government. The agreement provides for a multistep transition to democracy, beginning with the reunification of the country and the creation of an interim government that includes representatives of the rebel groups and the political opposition. The government will be responsible for drafting a new constitution and organizing general elections, to be held within two years.

Transitional Government Forms

The DRC’s interim government is installed according to the “1+4 model,” in which Joseph Kabila retains the presidency but shares power with four vice presidents drawn from the major rebel and opposition groups. While much of the country sees a return to normalcy, violence continues in the eastern Kivu and Ituri regions. The interim government proves unable to disarm the Rwandan Hutu fighters in the east, and the UN mission lacks the mandate to do so. Meanwhile, splinter factions of the RCD and Mai Mai militias continue to fight. By 2005, the MONUC force increases to fourteen thousand personnel, but its legitimacy is undermined [PDF] by the peacekeepers’ sexual abuse and exploitation of women and children.

Democratic Elections Are Held

The DRC holds democratic, multiparty elections for the first time in more than forty years. In a runoff held on October 29, President Kabila wins 58 percent of the vote, defeating former rebel leader Jean-Pierre Bemba. The elections are regarded as generally free and fair by international observers despite Bemba’s accusations of widespread fraud. Western donors contribute nearly $500 million for organizing the elections. MONUC provides security as former RCD leader Laurent Nkunda, who formed the splinter group CNDP in 2005, steps up his group’s attacks on eastern towns to try to disrupt the proceedings.

CNDP Rebels Agree to Peace

The central government reaches a peace deal with the CNDP rebels in March 2009 with the goal of converting them into a political party and integrating their fighters into the national army, the FARDC. The CNDP offensive launched in October 2008 had displaced hundreds of thousands of civilians in eastern Congo, and in January 2009, Nkunda had been arrested in a joint Congolese-Rwandan operation. Nkunda’s replacement as the head of the CNDP, Bosco Ntaganda, concludes the peace agreement with the DRC government.

Kabila Is Reelected in Disputed Vote

Kabila is elected to another term as president, winning 49 percent of the vote to opposition leader Étienne Tshisekedi’s 32 percent. International observers, including the U.S.-based Carter Center, say the voting is marred by a lack of credibility and transparency [PDF], and Tshisekedi refuses to accept the outcome. On December 16, the Supreme Court rejects Tshisekedi’s request that the results be annulled. Widespread opposition protests result in a crackdown by security forces that leaves dozens of people dead across the country.

M23 Crisis Leads to New Peace Accord

The war in the east resumes with the mutiny of former rebel CNDP soldiers who had been integrated into the national army. Naming themselves the March 23 Movement (M23), after the March 23, 2009, peace deal, the rebels take the largest city in the region, Goma, in November 2012. UN peacekeepers do not intervene. Nearly half a million people in the eastern Kivu regions are displaced by the renewed fighting. The crisis results in a February 2013 agreement between the DRC and ten of its neighbors known as the Peace, Security, and Cooperation Framework. The agreement commits countries in the region to noninterference in DRC affairs; a 2012 UN report had found that Rwanda and Uganda supported the M23 rebels.

M23 Warlord Ntaganda Surrenders to ICC

Bosco Ntaganda, leader of the M23 mutiny, turns himself in for trial at the International Criminal Court (ICC), which since 2006 had sought him on charges of war crimes. The surrender comes a year after the ICC sentenced an individual for the first time: eastern Congolese rebel leader and Ntaganda associate Thomas Lubanga. He received a judgment of fourteen years in prison for recruiting child soldiers. The ICC initiates public cases against six rebel leaders operating in eastern Congo, including two members of the largest Rwandan Hutu militia, for alleged crimes including the recruitment of children, rape and sexual slavery, and ethnic massacre. In 2019, the ICC finds Ntaganda guilty of eighteen counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity and sentences him to thirty years in prison.

UN Creates Offensive Force to Battle M23

The UN Security Council authorizes a new offensive force as an offshoot of the broader mission, renamed MONUSCO in 2010, after the M23 rebellion gains ground. The UN Force Intervention Brigade, numbering three thousand soldiers, immediately begins joint operations with the national army against M23. In November 2013, after displacing some eight hundred thousand people, seizing gold and other mineral resources, and committing atrocities across the region, M23 admits defeat and enters into talks to disarm and demobilize. However, thousands of fighters from myriad local militias and Rwandan Hutu forces continue to operate in eastern Congo with near impunity.

Protests Over Election Plans Turn Violent

President Kabila’s proposal to amend electoral laws sparks worries that he will defy constitutional term limits and run for a third term in the national elections scheduled for November 2016. The government cracks down on opposition protests in January 2015, with security forces killing at least forty people in Kinshasa and the eastern city of Goma. The opposition accuses Kabila of intentionally creating electoral “glissement,” or slippage, by pushing a major provincial redistricting plan that is likely to create administrative delays and keep Kabila in power. The newly appointed U.S. special envoy to the DRC, Thomas Perriello, immediately presses Kabila to commit to relinquishing power, while the head of the UN mission, Martin Kobler, says that the constitution “must be respected.” Kabila, meanwhile, makes no public statement on his intentions.

Postponed Elections Lead to Power-Transfer Plan

Officials announce that national elections will not be held by the November 2016 deadline, sparking widespread protest. After more than fifty demonstrators are killed in September, the United Nations warns that election-related conflict could rekindle the war in the DRC’s east, while the U.S. and European Union (EU) impose sanctions on Kinshasa. After initially boycotting talks, the largest opposition parties, backed by the country’s Roman Catholic hierarchy, agree to a power-transfer deal in which Kabila is to join a transitional government before holding elections and stepping down in 2017. However, opposition leader Étienne Tshisekedi, who had been selected to oversee the deal, dies in February 2017, leaving the opposition rudderless. Kabila eventually puts off elections until 2018, citing complications relating to registering more than thirty million new voters.

Washington Imposes Fresh Sanctions

The United States imposes a visa ban on several senior Congolese officials for corruption linked to the long-delayed elections, though it does not publicly identify the sanctioned individuals. It also sanctions Israeli billionaire Dan Gertler, a friend of Kabila, for corruption related to mining and oil projects in the DRC. The move comes a year after the U.S. Treasury Department levied sanctions on Kabila’s top military advisor, General François Olenga, and after the European Union imposed travel bans and asset freezes on eight senior Congolese officials and a militia leader for alleged human rights abuses, including some relating to military campaigns in the country’s east.

Kabila Confirms He Won’t Run

The Congolese government announces that Kabila will not run for a third term in an election set for December 23, two years after his mandate was slated to end. Instead, the ruling People’s Party for Reconstruction and Democracy (PPRD) backs Emmanuel Ramazani Shadary, Kabila’s former interior minister. The opposition vows to unite behind a single candidate, and in November opposition leaders agree to back businessman Martin Fayulu. However, Félix Tshisekedi, son of the late opposition figure Étienne Tshisekedi, and Vital Kamerhe, a former president of the lower house of Parliament, pull out of the deal and announce they will run on their own ticket. The electoral commission had barred several other popular opposition figures, including Jean-Pierre Bemba and Moïse Katumbi, from running.

Tshisekedi Takes Office After Disputed Elections

Long-postponed national elections take place on December 30, 2018, but official results are delayed for several weeks amid accusations of fraud. Election authorities ultimately declare Tshisekedi the winner, but election data acquired by Western media shows that opposition candidate Martin Fayulu garnered nearly two-thirds of the vote and won the eastern North and South Kivu Provinces, among others. Despite skepticism from the country’s Catholic hierarchy, regional organizations, and Western governments, Tshisekedi takes office on January 24, 2019, in the country’s first peaceful transfer of power since independence. The full government is not finalized until seven months later, with a power-sharing deal that gives members of Kabila’s party the majority of cabinet positions.

Kinshasa Responds to Growing Violence in the East

Tshisekedi moves to consolidate control, announcing a new cabinet dominated by his allies and purging Kabila supporters from the most powerful parliamentary posts. Analysts say this break with Kabila could mean the end of the political stalemate that has stymied reform efforts since the 2018 election, though it also risks destabilizing effects. With demobilization efforts stalled, Tshisekedi struggles to respond as simmering violence in eastern Congo escalates throughout 2021, including the killing of an Italian ambassador and protests against UN peacekeepers; Kinshasa ultimately imposes martial law in North Kivu and Ituri Provinces.

Revived M23 Spurs Regional Intervention

Remnants of M23 launch a fresh campaign in eastern Congo in March, citing a lack of progress on demobilization and Hutu armed factions in the region. Kinshasa appeals for help from the East African Community (EAC), a regional grouping of seven countries it joined that same month. The EAC organizes a multinational intervention force of some twelve thousand troops from Burundi, Kenya, South Sudan, and Uganda, which begins deploying in August. The DRC had already granted the Ugandan military permission to enter its territory in pursuit of the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), a militant group linked to the self-declared Islamic State. The fighting displaces more than a hundred thousand people, and in July, the UN mission’s failure to protect civilians prompts violent protests that lead to the deaths of at least thirty-six demonstrators and five UN peacekeepers.

DRC-Rwanda Tensions Deepen Over M23

With an M23 offensive threatening North Kivu’s capital, Goma, the DRC increasingly blames Rwanda for intervening to support the rebels. That accusation is backed by UN investigators but denied by Kigali. Nearly three hundred thousand Congolese are displaced by November, when the leaders of Angola, Burundi, the DRC, and Rwanda agree to a cease-fire in talks mediated by Kenya. M23, though not party to the talks, agrees to the truce but then fails to withdraw from its captured territories, accusing Kinshasa of continuing to support Hutu militias. In January 2023, the Rwandan military fires on a DRC fighter jet that it says violated Rwandan airspace. Kinshasa says the move “amounts to an act of war.” By the end of January, the number of displaced people in eastern Congo surpasses 450,000.

Pope Francis Urges a Return to the Peace Process

The Catholic pontiff’s four-day tour marks the first papal visit to the country since 1985. About half of the DRC’s population of roughly one hundred million is Catholic, and church leaders have long played a central role in politics, including by organizing election monitors and speaking out against democratic backsliding. Francis presides over one of the largest-ever Masses, attended by nearly one million people, and in a speech to the country’s leaders, he calls for elections scheduled for December 2023 to be “free, transparent, and credible.” He also condemns what he calls the “economic colonialism” of the trade in diamonds and other conflict minerals and exhorts the DRC’s warring factions to recommit to the peace process. Initially scheduled to visit the country’s war-torn east, the escalating violence there leads Francis to meet with victims of the conflict in Kinshasa instead.

Tshisekedi Pushes for Peacekeeper Withdrawal as Displacement Spikes

Addressing the UN General Assembly in September 2023, President Tshisekedi announces that he will ask the UN peacekeeping mission, now numbering some seventeen thousand troops, to move its planned departure to December 2023, a year ahead of schedule. Despite operating for more than a quarter of a century, the peacekeepers have “failed to cope with the rebellions and armed conflicts” as violence and civilian displacement worsened, Tshisekedi says. In October 2023, the International Migration Organization (IOM) reports that the number of internally displaced people in the DRC has reached a record high of 6.9 million people, with more than 80 percent being in the country’s east. The IOM says that “the DRC is facing one of the largest internal displacement and humanitarian crises in the world.”

Peacekeepers Pause Withdrawal as Fighting Continues

After initially pulling several thousand troops, MONUSCO puts its planned end of year departure on hold over what the DRC government calls Rwanda’s increasing intervention in the eastern provinces, while Kigali continues to accuse Kinshasa of supporting and sheltering FDLR fighters that threaten Rwandan territory. Talks hosted by Angola fall apart by the end of the year, and Rwanda-backed M23 fighters disregard a cease-fire agreement. By July, the Southern African Development Community, a regional organization, has deployed around eight thousand troops to the area as part of an effort to help defeat M23, though some observers say the mission could further escalate the conflict with Rwanda. Meanwhile, antigovernment protests continue over the sharply deteriorating humanitarian and security situation—the United Nations says the number of displaced people now tops 7.3 million and more than one hundred thousand have been subject to sexual violence by formal and informal armed groups. In May, the army staves off a coup attempt against Tshisekedi.

M23 Captures Goma, DRC Accuses Rwanda of Declaring War

M23 rebels claim they’ve captured the eastern city of Goma, a longtime humanitarian hub, stifling critical routes for travel and aid. Increased fighting around the city prompts protests in Kinshasa and attacks on several embassies, including the United States, Belgium, and France, in anger over the international community’s failure to stop the rebel advance. The UN Security Council plans an emergency meeting, and African neighbors also begin to convene over the matter. The DRC foreign minister accuses Rwanda of declaring war by sending troops over the border to support the M23.

Online Store

Online Store